Quality attributes such as performance, security, resilience, scalability and maintainability frequently determine whether a system remains viable over time, yet in many organisations they are consistently overshadowed by the drive to deliver new features.

This tension has existed for decades, and while the industry continues to adopt new practices, methods and technologies at pace, the fundamental challenge remains: Quality attributes (QAs) require system-level attention, but the structures and incentives within most delivery environments are not naturally aligned to prioritise them.

This post explores the reasons behind this persistent imbalance and considers how architecture practices can bring QAs back into focus through clearer reasoning, better communication, and more deliberate decision-making.

“How many stories in this sprint?“

The preferences of business and product stakeholders naturally gravitate towards features because these are tangible, demonstrable and easy to map to customer value, commercial opportunity or immediate regulatory demands. Features appear in roadmaps and quarterly plans; they can be shown in demos, and they often form the basis for performance reporting at the team, product and organisational level. Quality attributes, by contrast, are largely invisible until they cause problems, at which point the consequences, which can include slow response times, outages, security incidents, and compliance failures, are both significant and often expensive.

Because the impact of a feature can be observed immediately, whereas the impact of a performance improvement or a resilience enhancement is only visible under specific conditions, features invariably attract a greater share of attention and become the priority. The result is that QAs, although universally agreed to be important in principle, are repeatedly deferred until some later point when they become unavoidable, usually in less favourable circumstances. How many times have you heard in sprint planning discussions “Yes, I agree, performance is absolutely crucial, but I don’t think we need to do it in this sprint.” And then in the next sprint we hear similar sentiments, and quite possibly the next, until something goes critically wrong and needs immediate attention.

Cross-cutting concerns without clear ownership

One of the fundamental challenges is that quality attributes do not sit neatly within the remit of a single team. They have to be addressed at system level and so require coordination across multiple components, teams and priorities. Security cannot be left to one group; resilience demands consistency across many subsystems; logging and observability are only valuable when implemented consistently; and scalability often emerges from architectural decisions that span whole areas of the solution rather than any individual part.

Because no single team is explicitly accountable for these qualities, and because each team is typically driven by product-centric delivery expectations, quality attributes quickly lose priority. Individuals focus on what they are directly judged on (namely feature delivery) and avoid incentivising their teams to take responsibility for system-level concerns that they cannot influence alone. The result is a gradual collective deprioritisation.

Why architects and tech leads inevitably assume responsibility

In this environment, the technical leaders typically assume responsibility for articulating and maintaining the system’s quality attributes. This is probably inevitable because they hold the broad system-level view, ensuring that short-term delivery pressures do not compromise essential long-term systemic qualities.

In many respects, someone like an architect, or the technical lead team, become the organisation’s technical conscience, identifying risks that others do not easily see and articulating the consequences of deferring key architectural work.

This responsibility is both structural and necessary. Without a group or individual who can advocate for system-level quality, the accumulation of technical debt, design fragmentation and operational fragility becomes almost inevitable.

Securing stakeholder understanding and support

Although architects may initiate the focus on quality attributes, progress is only possible when stakeholders understand and support the underlying rationale. Quality attributes need to be reframed as business concerns rather than purely technical aspirations, because it is the relationship between system behaviour and business outcomes that ultimately drives prioritisation decisions.

This requires clarity, patience and a willingness to explain not only what the system must do under expected conditions, but also how it behaves when circumstances depart from the norm, whether through load, failure, misuse or unexpected complexity. Stakeholders do not need to become experts in the underlying mechanisms, but they do need to appreciate the operational, financial and reputational implications of deficiencies in key attributes.

The value of scenarios in communicating quality attributes

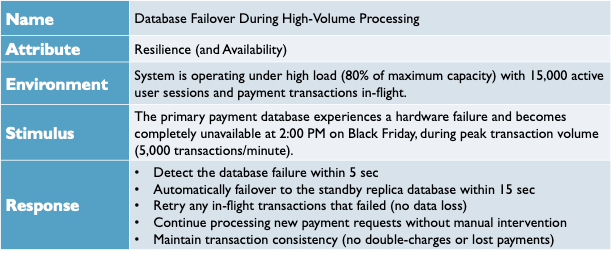

One of the most effective mechanisms for making quality attributes concrete is the use of structured scenarios. A scenario describes a specific situation in which a quality attribute is tested, and it typically includes a stimulus, a defined environment, an expected system response and an outline of the associated trade-offs. By anchoring the discussion in a recognisable operational context, scenarios make the implications of QAs far more accessible.

For example, a simple resilience scenario involving a database server failure during peak load is shown below:

I’ve simplified this a little in the interests of space, but I think it still captures the essence of a good quality attribute scenario.

By stating that the primary server hangs unexpectedly at a defined time, that the system is processing transactions for thousands of concurrent users, and that the desired behaviour is to detect the failure within a few seconds, fail over automatically, preserve user sessions and maintain operations with minimal disruption, we move the conversation from abstraction to operational clarity. Stakeholders can now see exactly what the system must do, why it matters, and what would be at risk if such behaviour were not in place.

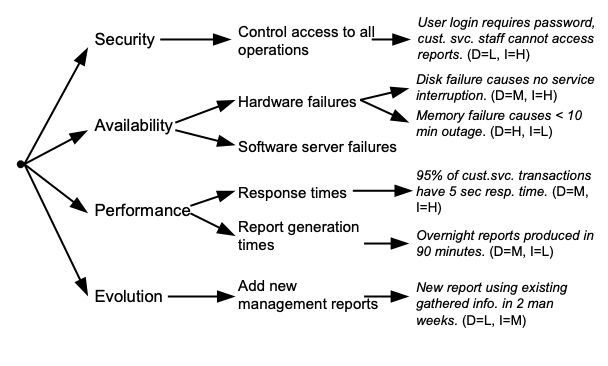

Given their usefulness, you often end up with quite a few different quality attribute scenarios to illustrate the system’s required behaviour in different situations. A useful technique for organising multiple scenarios is the quality attribute tree, which helps to gather the scenarios into a quality attribute oriented structure, to allow you to identify priorities and reveal gaps. A simple example is shown below:

As can be seen from the example, this simple technique, which was originally introduced as part of the ATAM architectural assessment method, helps to organise a set of quality attribute scenarios, indicating clearly which quality attribute and specific requirement each illustrates. The scenarios are also annotated with their importance (“I”) and difficulty (“D”) rated as high (H), medium (M) or low (L) to provide an idea of their relative priority and scale.

Turning quality attribute concerns into manageable work

As previously explained, implementing quality attributes often involves large, complex pieces of work, that can be perceived as incompatible with short iterative delivery cycles. Therefore, an important task is helping teams decompose these major system-level changes into smaller, actionable pieces of work that can be incorporated into existing backlogs without disrupting the broader delivery flow.

This involves identifying relevant architectural tactics, translating them into specific tasks, and working with product owners to ensure that these tasks receive appropriate priority. Tactics arise from many sources, including books and catalogues, established communities such as OWASP for security, specialist websites, including those dedicated to performance or scalability, organisational knowledge and individual experience. Each tactic addresses a particular concern within a particular context, and each carries its own set of trade-offs.

Some areas, such as resilience, disaster recovery and business continuity, often require senior leadership and co-ordination across the organisation, while other quality attributes may be more easily delegated or championed by team members with relevant expertise. In all cases, visible alignment with the scenarios that describe the required outcome ensures that the work is understood and justified.

Explaining trade-offs with appropriate analytical tools

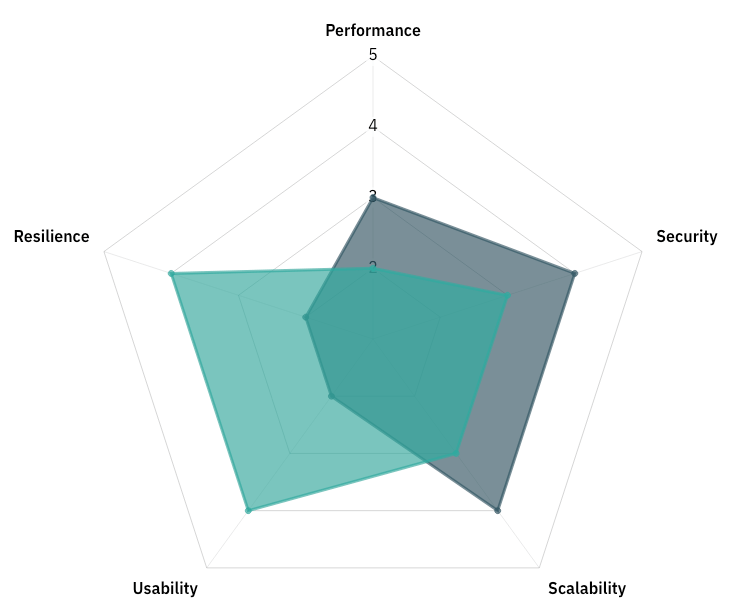

Quality attributes rarely exist in isolation. Enhancing one attribute often introduces constraints on another, and meaningful architectural decision-making involves recognising and explaining these trade-offs. For instance, security improvements can reduce usability; increasing scalability can increase operational complexity; and pursuing cost efficiency can constrain performance or resilience.

To support this analysis, architects can draw on a range of visual and analytical tools. Trade-off matrices help structure the evaluation of alternatives and make the reasoning behind decisions explicit. Scenario interaction maps reveal where scenarios reinforce or conflict with one another. Stakeholder–scenario matrices highlight which groups place the highest value on particular outcomes. Radar charts can be used to compare architectural options across multiple attributes, illustrating the relative strengths and weaknesses of each candidate design.

A simple example of a radar chart, showing how two architectural options involve tradeoffs between resilience, performance, security, scalability and usability is shown below.

I will make more examples of these techniques, along with worked scenarios, available in future posts or on my website for anyone who wishes to use or adapt them in their own work. I have found that they useful in giving teams a practical starting point for analysing system-level trade-offs.

The enduring quality-attribute dilemma

The underlying dilemma persists: quality attributes are often the determinants of long-term system success, yet they routinely receive less attention, priority and resourcing than features.

Yet, if organisations wish to build systems capable of evolving, scaling and operating reliably, they must confront this tension.

The experiences and tools are available to help, and we know that a logical and organised approach can help teams ensure that QAs remain in focus. Prioritisation, scenario-driven clarity, cross-team coordination and disciplined trade-off analysis are useful contributions to this work.

When we lead with the continuous architecture approach of transparency, structure and shared reasoning, we provide a foundation on which teams can make principled decisions and deliver systems that remain robust over time